Heart disease prevention

US: Prevention and regulation

People-chow and 'fresh fruit' on sale in an Orlando 'supermarket', and (right) on-tap choices for delegates at the American Heart Association conference

Orlando, Florida. Geoffrey Cannon reports: The American Heart Association held its annual scientific sessions between 12-16 November in the magnificent Orange County conference centre in Orlando, Florida. One admirable initiative was its programme on 'Global cardiovascular prevention and health promotion', which ran throughout the congress.

Chair and co-chairs of this initiative were three visionary leaders: Donald Lloyd-Jones of North-Western University, Chicago; World Heart Federation president Sidney Smith of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and Public Health Foundation of India president Srinath Reddy. To them all praise and thanks for their foresight.

What happened

I participated as a speaker in an afternoon session on the first day – and also as a contributor to other sessions. Fellow speakers in the first day session included David Jenkins from Toronto, famed for the glycaemic index; Dariush Mozaffarian of the Harvard School of Public Health, a colleague of Association member Walter Willett; and Michael Jacobson, founder-director of the Centre for Science in the Public Interest. Our theme was 'Food: How could we make it healthier?' I was asked to speak on legislation and regulation, especially on the hot topic of the advertising and marketing of ultra-processed products to children.

There was plenty of discussion throughout all the 'global' sessions on primordial prevention, a term used to identify ways of prevention that are in no way medical. Outstanding speakers included Darwin Labarthe from Atlanta, Trevor Hassell from Barbados, Frank Sachs from Boston; and Simon Thorn from London, who 'lost' a scintillating debate in which he advocated the individual 'polypill' versus the population 'polymeal' championed by Dariush Mozaffarian of the Harvard School of Public Health, a superb researcher, presenter and speaker.

So what?

At the time and afterwards, I gained four impressions. The first as always, is just how very well-organised clinical- and medical-orientated congresses are, held in the US. The 567-page programme listed over 6,000 moderators, speakers and abstract presenters. This represents an enormously important contribution to cardiology training and career development, including very bright young people from all over the world now based in the US. This has to be a big factor in the dramatic drop in cardiovascular disease mortality, if not morbidity.

Second, and this may be a reflection of my own 'prism', with some exceptions, presentations on prevention carefully stuck to the concept of 'individual lifestyle adjustment', and therefore separated what a person might choose to do, and what government at any level could support populations, communities – and people – to do. My own presentation quoted an agreement made at Srinath Reddy's institute in 2008, that 'all significant improvements in public health require and involve the use of law. There is no exception to this rule'.

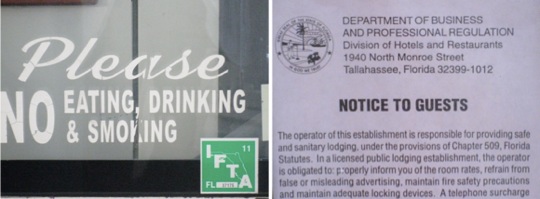

In support of this 'Hyderabad Statement' I pointed out that in so many ways, US citizens are supported by regulation. I always try to give down-home examples of this, such as a polite sign on the bus I took from my hotel to the congress centre, and the notice on the back of the door of my hotel room, shown below.

The US remains a tightly regulated country, as shown by notices like this. Official ideology, applied to public health, is to 'leave it to 'the market'

So why are public-spirited health professionals based in the US so shy of mentioning the need for law and regulation in our field of public health? A number of senior people at Orlando, having thanked me for what I presented, explained.

Taken together, they said that with some very senior, retired, outlaw or brave exceptions, the profession divided into two groups. One believed that health and its care should be private and that government has no or only a residual role. The other remains convinced that the maintenance and improvement of public health is a defining characteristic of government at all levels, but dare not say so, because their funds, or those of their department or place of learning, come from donors whose ideology or profits are all about the privatisation of public health.

My third impression was of where we were. Orlando is not the US, but there we were. It is very cheap to eat in Orlando, unless you are fussy. At the beginning of this piece here (left, above), you see a picture of a 20-pack plastic sack of PepsiCo snacks. When I first saw it in an aisle of a 'supermarket' I thought it was dog or cat chow. No, it is people chow. In the same 'supermarket' I looked for fresh food and what I found is shown (middle, above).

'Then I prowled around the fast food joints in the congress centre servicing the delegates in what seems to be a Pepsi state (with all the deals implied) and what I found was Pepsi on tap for craving cardiologists (right, above). The picture (right) on the home page introducing this item, shows that all customers at an eat-all-you-want for $US 10 or so pizza parlour down the road a'piece could also chug-all-you-want Pepsi. These places to me seemed like gas stations, with the important exceptions that (a) once you had signed your card for a small amount you could fill up as much as you liked and (b) your tank expanded – hence explosive obesity. But then, I was only a visitor.

The fourth impression? As we checked out of the Econolodge, a focused young Indian delegate greeted me. It turned out that we had met before not in Orlando, but Hyderabad. He told me that he was moving from cardiovascular disease to diabetes. You mean, because diabetes is on the up? I asked. Yes, he said, far more opportunities.