As I see it

Philip James

Access Philip James's profile here

London. We live in a world where the elected governments of most powerful countries are ceasing to do their duty to protect public health and the public interest. Instead, they 'leave it to the market' – meaning big business, as amplified by the media, which is also a big business. Please don't get me wrong. Progress requires engagement with industry. But that's different from surrender to the profit motive.

In writing my first story below, on attempts to confront obesity in my country, I was reminded that before first becoming an elected politician, the current UK Prime Minister was for eight years, corporate affairs executive for a commercial television company. I am also reminded this month that the race to the US presidency is not the prerogative of the Olympians, but is usually won by the candidate who raises most funds in particular from corporate sources. This is the world in which we try to defend the public interest and public goods. We need industry. We also need balance, and we need elected governments that hold that balance in a way where business can flourish but without damaging and preferably promoting public health.

Obesity. The UK 'responsibility deal'

Privatisation of public health

This month I am trying to work out what officials and professionals in local government can do to combat the awful impact of obesity on the UK population. This is needed more than ever now that the current UK government has moved the major responsibility for meeting public health targets from the national to the local level. What is going on? There is a context here – there always is.

Responsibility for obesity

Three years ago, soon before the general election as a result of which the UK government became dominated by the right-wing Conservative Party led by David Cameron (now UK Prime Minister seen on the left in the picture strip below), my colleagues in the International Obesity Task Force were asked to go to meet the 'shadow' minister of health, David Cameron's colleague Andrew Lansley (next picture). He was clearly very knowledgeable, and had read the UK Chief Scientist's Foresight report on obesity (1), which describes all the factors promoting the epidemic. However, the meeting was interrupted by David Cameron, who came into the room and made clear that for him, the concept that multiple societal and environmental factors were responsible for the obesity epidemic was nonsense. Obesity 'was an individual responsibility', as he soon emphasised in a public speech. He told the IOTF team that he would do nothing, in any way, to impede the enterprise of the UK food manufacturing and allied industries. You can read more about this here.

Sure enough, soon after David Cameron became Prime Minister in May 2010, Andrew Lansley, as Minister of Health, excised the nutrition department from the prestigious and reasonably independent Food Standards Agency (FSA), as demanded by the Food and Drink Federation, the body that represents the interests of UK and international manufacturers. From then on he directly controlled any policy proposals or announcements, because the potentially troublesome nutritionists and public health experts in the FSA were either removed or else placed within the Department of Health.

He then sacked the government's expert advisory group on obesity (2), and partnered with the leaders of the food and drink industries in a so-called 'Responsibility Deal', where manufacturers agreed to a voluntary arrangement to improve the nutritional profile of the UK food supply in order to counter obesity and its associated chronic non-communicable disease burden.

In response Hugh Stephenson of the UK Academy of Royal Medical Colleges said rather mildly: 'Doctors think it's inherently unlikely that huge companies that make money from selling high-calorie foods and drinks, like McDonald's and Coca-Cola, are going to persuade their customers [to eat more healthily]. It's like asking the petrol companies to say to people, "why not go on your bicycle?" It just does not seem likely that's going to happen.'(3).

When I lecture to leaders of the medical profession in the UK, I am continually astonished at how naïve they are and how ignorant of such political skullduggery. More importantly, when I talk with groups of public health specialists, they wonder what on earth they can do, now they are being completely reorganised in the context of a monumental reconfiguration of the whole National Health Service. This is designed to bring the NHS into the 'market economy'. Responsibility is being removed from central government. Instead, competitive tendering for health services is being imposed, the deal being that commercial companies that win bids will be guaranteed a slice of the action.

Health and public duty

Here in the UK the politicians now in office believe that government should withdraw from the provision of public services, and that what works most effectively and efficiently is private provision. The justification for this approach is said to be experience in the US. However, in World Health Organization reports on effective and efficient national health provision (4), the US ranks far down the list. Its provision is assessed at more or less at the same level as for example Brazil, Poland, Greenland and (pre-second invasion) Iraq, and as inferior to that for example of Algeria, China, Venezuela and Iran.

UK (left), David Cameron, Andrew Lansley: for industry. US (right), Michael Bloomborg, Thomas Farley: for regulation. Where is the man in the middle?

So what can I say to the public health workers who are now suddenly being assigned to local government? Is the situation hopeless? Fortunately there is good evidence that all is not lost as we learn from within other countries where commercial interests also dominate and effectively control health and economic policy making.

The New York example

The US is an example. There it is taken for granted that public health measures do follow powerful legal challenges to existing practice, or else as a result of grass roots action demanding change at a community level. In the US everybody knows that the legislators in Congress are controlled by big business. The President will not make a move, and his First Lady, while calling for change and fully understanding the economic drivers of the obesity epidemic, is facing impossible odds and has no legislative role.

But in the US there is effective action at big city level. It is illuminating to see the initiatives that Michael Bloomborg (second from the right in the pictures above) as mayor of New York City, who ironically is a multi-billionaire, is taking. His public health team is banning trans fat in the food chain, requiring calorie labelling of menus in canteens and restaurants, and limiting the size of soft drink containers where the City has jurisdiction. As I discovered in discussions with the Bloomborg Foundation in New York, there is a very clear understanding that reliance on individual choice, for example to limit smoking or reduce road traffic accidents, does not protect public health. Now Michael Bloomborg, through his foundation, has started to take on the obesity problem internationally, as well as in New York City.

Could it happen here? Can we turn to the man in the middle in the pictures above? This is Boris Johnson, the mayor of London, a flamboyant right-wing politician with a flair for publicity and rhetoric, and for annoying the current government. He has said that he plans to emulate mayor Bloomborg's initiatives. Thus: 'A superb 2012 legacy for London would be the obliteration of childhood obesity. We are championing effective plans across the capital to fight this, and I hope that working with New York will result in leaner, fitter children and families in both our cities. I want to take on the fast food companies who mercilessly lure children into excessive calorie consumption. Instead of junk snacks let's encourage kids to grow their own food…We must also help the poorest communities who are most vulnerable to bad diets of poor quality food. A key part of my health inequalities plan is to increase access to affordable healthy alternatives' (5).

Strong words. He spoke them before David Cameron took over as prime minister in the UK. Is he serious? (6). I am also reminding public health groups in the UK that before the introduction of the 1948 National Health Service, in every city the Chief Medical Officer of Health was the most important policy maker and controller, after the mayor or council chair. Is this the new model? Thomas Farley, the man by Michael Bloomborg's side above, who is the New York City Health Commissioner, has a powerful post.

So what can be done now, within cities? For a start, soft drinks and junk food generally can be excluded from all publicly funded or supported institutions, plus other measures designed to protect deprived and impoverished communities. In the UK, a new local government law also enables communities to set out their vision for statutory future planning policies. This could transform cities over time. Local action can improve food supplies and what people eat in publicly funded schools and institutions, by limiting large serving sizes, stopping the serving of inappropriate foods, and pricing policies that favour the supply of healthy foods

So perhaps the lesson to be learned from the surrender of national government to commercial interests, is to start again, and focus on working with cities whose elected officials have statutory powers. In my country this can start now, with reference to the good work being done in New York and many other US cities. But we all need to be aware of the realities of democracy in its current form. We also can't rely on politicians who are so wealthy that they can finance their own campaigns. Elected politicians may know what is right and what is wrong, but those in government typically will only back reforms that they think will win them more votes next time round. Are we prepared to commit ourselves to the task of projecting what is correct, and what is right, in ways that are compelling and popular? I hope so.

References

- The Foresight Report. Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Modelling, Future Trends in Obesity and their Impact on Health. Second edition. UK Government Office for Science, 2007.

- Stacey K, Lucas L. Obesity panel disbanded amid claims of bias. Financial Times, 16 November 2011.

- Campbell D, Boffey D. Doctors turn on No 10 over failure to curb obesity surge. The Guardian, 14 April 2012.

- Evans D, Tandon A, Murray C, Lauer J. The Comparative Efficiency of National Health Systems in Producing Health: an Analysis of 191 Countries. GPE discussion paper 29. EIP/GPE/EQC. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000.

- Greater London Authority. Mayor of London joins forces with New York to battle childhood obesity. Media release 25 January 2010. http://www. london.gov.uk/ media/press.releases.mayoral/mayor-london-joins- forces-new-york-battle-childhood-obesity.

- Hastings M. Brilliant, warm, funny – and totally unfit to be PM. The Guardian, 11 October 2012.

World aid. Copenhagen Consensus 2012

Drugs, surgery and education are not enough

The Copenhagen Consensus on smart ways to save the world, in process

of taking shape, with a panel of US Nobelists advised by technical experts

These are indeed interesting times for all of us who currently engaged in public policy. Take 'The smartest ways to save the world', perhaps this year's most self-confident op-ed headline. Published in May this year in over 400 newspapers round the world (1), it heads a piece by Bjørn Lomborg, (below, left), who in 2001 was identified as a 'global leader for tomorrow' by the World Economic Forum. Adjunct professor at the Copenhagen Business School, he is a climate change sceptic, which he characterises as 'not the end of the world' (2).

Describing himself as an 'intellectual entrepreneur', he is also founder and director of the Copenhagen Consensus initiative. Funded originally by the Danish government and co-sponsored by The Economist, the idea is to come up with the best researched, most rational and promising independent answers to the great issues that confront us. The first initiative in 2004 gave a special priority to HIV-AIDS (3). The top priorities in 2008 were providing vitamin A and zinc supplements to impoverished children, liberalising trade, fortifying salt and staple foods with iodine and iron, and expanding childhood immunisation; cutting greenhouse gases was bottom of the list.

The 2012 initiative has been on how best to spend aid money, given all the competing priorities. Recently I participated in a meeting here in London setting out the basis for the newly published 'Copenhagen Consensus 3'.Rachel Nugent (below, right), previously of the Center for Global Development in Washington DC, now associate professor and director of the Disease Control Priorities Networkin Seattle at the University of Washington's Gates-funded Department of Global Health, explained to us her work in helping to prepare and run the process which led to the latest Copenhagen Consensus (4).

First, the main topics are chosen. For 2012 these were armed conflict, biodiversity, chronic disease, climate change, education, hunger and malnutrition, infectious disease, natural disasters, population growth, and water and sanitation. Corruption and trade barriers were added but not analysed, the reason given being 'because the solutions to these challenges are political rather than investment-related'. This seems to imply a preconception favouring money as the most effective way to do good in the world.

Of the top ten chosen challenges for the Copenhagen Consensus, we can count three as clear concerns for public health nutritionists: chronic disease (also now known as NCD); hunger and malnutrition; and also infectious disease. For the 2012 Copenhagen Consensus process,as background and as a basis for decisions and judgements, high-quality 'challenge papers' were prepared. These are all well worth reading. You can access the paper on chronic disease here, that on hunger and malnutrition here, and that on infectious disease here. Of the twelve authors, seven were based in the US, either in Washington DC or Washington State, three in Canada, and one each in the UK and India.

The 2012 Copenhagen consensualists: Vernon Smith, Robert Mundell, Thomas Schelling, Finn Kydland, Nancy Stokey, all economists from the US

The next standard part of the process was to assemble a panel of eminent economists. As stated on the official website (4): 'The Expert Panel will look at all of the solutions to all of the problems, and identify the most cost-effective ways of achieving good in the world. The final outcome will be a list of priorities with all the solutions identified by the scholars ranked by the expert panel according to the potential of each solution for solving the world's greatest challenges most cost effectively'.

The judges chosen by Bjørn Lomborg and his team for the 2012 process were five distinguished economists, all working in the US, three of whom are US citizens These, shown in the picture strip above from left to right, included four venerable Nobel Prize winners: Vernon Smith, Robert Mundell, Thomas Schelling and Finn Kydland, with an average age of 80, and also Nancy Stokey. In a sense the US dominance is unremarkable: 34 of the 38 winners (all but one male) of the Nobel economics prize since 1992 are US citizens or else US-based. The ideology of the 2012 judges is mostly monetarist.

They were convened in Copenhagen in May with a challenging brief to 'change the game'. They were asked to judge what major benefits to society would emerge if they could decide how to spend an additional $US 75 billion, which is 15 per cent on top of the current total global aid budget, over a four-year period. They evaluated the evidence from the challenge and other background papers. They sat with technical and other expert advisors and reasoned together, as in the picture below, which shows Vernon Smith of Chapman University, California, making a point, watched by Nancy Stokey of the University of Chicago, with Thomas Schelling, previously of Yale and Harvard, now of the University of Maryland, also in the picture.

2012 Copenhagen. Economic Nobelist Vernon Smith emphasises a point, watched by Nancy Stokey. Also in the picture, left, is Thomas Schelling

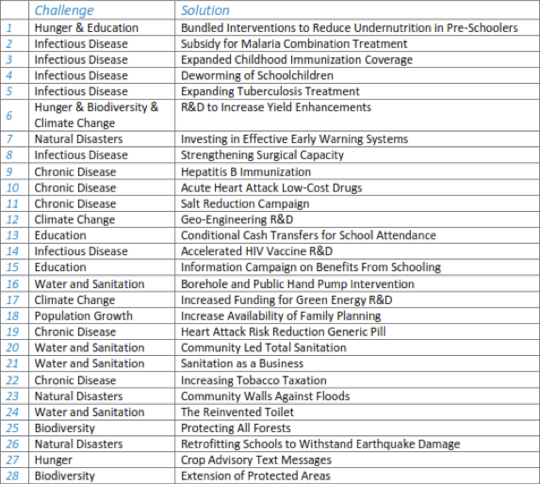

Table 1 below, shows the 2012 Copenhagen Consensus conclusions, ranked in order, on the most cost-beneficial policies and actions in the ten selected areas.

Table 1. 2012 Copenhagen Consensus

The most cost-beneficial policies and actions

designed to improve human welfare

Judgements made by the 2012 Copenhagen Consensus group of Nobel

Economics Prize laureates, supported by background 'challenge papers'

As you see, childhood malnutrition features prominently (#1,3,4), with food production and supply issues (#6), and water supplies and effective sanitation (#20,21,24), are still recognised as priorities. For chronic diseases the panel was evidently most impressed by the apparent promise of low cost drugs for heart attacks (#10), and the chronic use of the polypill (#19). Hepatitis immunisation was specified, to reduce liver cancer (#9). The panel also identified tobacco taxation (#22), and salt reduction campaigns (#11).

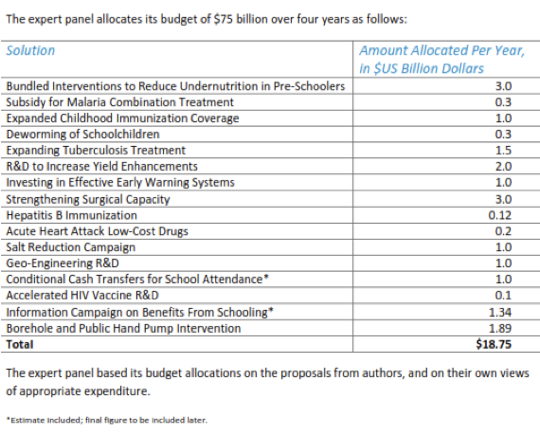

They concluded that they would spend each year for the specified four-year period, the following amounts, just on the first 16 priorities, as shown below in Table 2. This is what Bjørn Lomborg positions as 'the smartest ways to save the world':

Table 2. 2012 Copenhagen Consensus

The best use of money to help resolve

the world's biggest challenges

Annual budgets for four years, in order of priority

Given their training, their beliefs, the nature of the background papers, and the brief they were given, it is not surprising that the economists chose 'near-market' interventions, likely to generate direct evidence of an effect. For addressing hunger and malnutrition, where papers have been developed from decades of discussion and assessments, these can indeed be effective. For instance, immunisation programmes (#3), cash transfers for school attendance (#13) borehole and pump interventions (#16), as well as conventional 'bundles' of interventions (#1) are known to work.

But in the area of chronic non-communicable diseases, the 2012 panel has merely made proposals for medicine and surgery (low cost drugs for acute heart attacks, #10, strengthening surgical capacity, #8) and information and education (campaign for salt reduction, #11). There seemed to be no thinking about the social determinants of health and disease, or of issues of equity and sustainability.

Participants at our London meeting were dismayed. Are economists, however eminent, always the best judges of world issues that involve equity, human rights, social and environmental upheaval, and other matters in which money and income is just one factor? But even if they are, we wondered why Bjørn Lomborg and his team continued to select economists who as a group favoured monetarism and the Washington Consensus.

There are other more broad-minded economics Nobelists who could have judged the evidence and also advised on what evidence is most relevant. Five, all now based in the US, are pictured below: Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, Daniel Kahneman, Robert Fogel (pictured with his late wife), and Amartya Sen (former Master of King's College, Cambridge). Such a panel might well have had a more lively discussion and come up with more imaginative lists of priorities. Indeed, such a panel would almost certainly have challenged some of the principles underlying the Copenhagen Consensus process.

Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, Daniel Kahneman, Robert Fogel (with wife),

Amartya Sen: Nobelists not engaged in the Copenhagen Consensus process

This year's Copenhagen Consensus 'challenge' and other background papers highlight the need for the authors of such work to be familiar and sympathetic with broader analyses, and to have easy access to such work. In our field these should show the impact on health and potential reversibility of disease by means of diet and nutrition, for example through strategic measures such as changes in the food supply, or in the relative cost of different commodities.

Without such analyses it is no wonder that the 2012 Copenhagen Consensus Nobelists ended up relying on enthusiasm for poly-pills and other measures often backed by trials funded by interested industrialists. It is a pity that they were not offered the Simon Capewell analyses I referred to last month (5), which show that preventive interventions can show greater benefit than treatment strategies with the effects becoming apparent within a very few years.

The fact that the 2012 Copenhagen panel did not set out coherent intersectoral policies was not because they are economists. It was because as a group they were narrow-minded economists with apparent little feeling or sympathy for what economics as a social science should really be about, especially in the context of low and middle income countries.

For example, changes in trade agreements can alter major factors affecting health –particularly food. This emerged for me clearly in the first major meeting of the Caribbean Heads of State which eventually led to the UN high-level meeting on chronic non-communicable diseases in September last year. Vincent Atkins, an economist who is trade advisor to CARICOM, the Caribbean Community Secretariat, stated that trade policies have not really considered public health nutrition at all, and there are ample opportunities for adjusting agreements within the current World Trade Organization rules. This eventually led to a detailed analysis of trade, food and health in all its dimensions as set out in a book published in 2010.

We should get a grip on this. How very much more work we in public health nutrition need to do.

References

- Lomborg B. The smartest ways to save the world. Project Syndicate, 16 May 2012. http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/the-smartest- ways-to-save-the-world

- Lomborg B. Cool It: The Skeptical Environmentalist's Guide to Global Warming. New York: Random House, 2007.

- Lomborg B. Global Crises, Global Solutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004

- The Copenhagen Consensus of 2012. http://www.copenhagenconsensus . com/Projects/CC12/Outcome.aspx)

- Ford ES, Capewell S. Proportion of the decline in cardiovascular mortality disease due to prevention versus treatment: public health versus clinical care. Annual Review of Public Health 2011, 32 :5-22.