World Nutrition

Volume 3, Number 3, March 2012

Journal of the World Public Health Nutrition Association

Published monthly at www.wphna.org

The Association is an affiliated body of the International Union of Nutritional Sciences For membership and for other contributions, news, columns and services, go to: www.wphna.org

Commentary.

Sexing up

ultra-processed products

Jean-Claude Moubarac

Centre for Epidemiological Studies in Health and Nutrition

University of São Paulo, Brazil

Biography posted at www.wphna.org

Email: jean-claude@usp.br

Access pdf of November commentary (main thesis) here

Access pdf of January commentary #1 (profiling, soft drinks) here

Access pdf of January commentary #2 (Food Guide Pyramid) here

Access pdf of February commentary ('carbs') here

Access pdf of March commentary (nutrition labelling) here

Access pdf of April commentary (hydrogenation) here

Access pdf of May commentary (first of two on meals) here

Access pdf of June commentary (second of two on meals) here

Access pdf of August commentary (ultra-processed products) here

Access pdf of November commentary (bread and hot dogs) here

Access pdf of editorial linked with this commentary here

Access the pdf of this commentary here

Introduction

Editor's note

This commentary by Jean-Claude Moubarac resumes our series of commentaries on food processing, and its impact on public health, public policies, society and the environment. The general thesis of the series, originated within the school of public health at the University of São Paulo, is as follows. 'The most important factor now, when considering food, nutrition and public health, is not nutrients, nor foods, so much as what is done to foodstuffs and the nutrients originally contained in them, before they are purchased and consumed'. The next in the series will be published in our May issue.

In this commentary, company and brand names are used, but only as examples of general tendencies in historic and modern food and drink advertising. The commentary is the opinion of its author. It is not, and should not be taken to be, comment on or criticism of any specific company or brand. The points made are generic.

In the first commentary in this series, Carlos Monteiro sets out the beginnings of a new general theory about the nature of public health nutrition. As he puts it: 'the big issue is food processing – or, to be more precise, the nature, extent and purpose of processing, and what happens to food and to us as a result of processing' (1). In the commentary a new classification, developed with colleagues, is presented. This separates unprocessed or minimally processed foods (Group 1), from culinary ingredients (Group 2) and from ultra-processed products (Group 3). Subsequent commentaries examine the differences between these three groups, and why ultra-processed products, when consumed in large amounts as they now are in most parts of the world, are a likely prime cause of epidemic and pandemic obesity and various chronic diseases (2-5).

The commentaries are also wide-ranging. They consider social, cultural, economic, political, and environmental as well as biological aspects of processing and in particular ultra-processing. For anybody with a view of foods that goes beyond the nutrients they contain (or do not contain), this is refreshing. Food engages with very many aspects of life (6). Other issues addressed in the commentaries published so far include the failure of nutrient labelling (7), problems with the US Food Guide Pyramid (demolished a few months later) (8), and the importance of meals and commensality (9).

Nutrition seen mainly as a biological science is not enough. Only a broad approach can explain the impact of food systems and dietary patterns on human health – let alone all their other types of impact. Here I introduce a topic not often touched on in nutrition journals or indeed elsewhere. This is the nature of the advertising of ultra-processed products, and its likely impact on patterns of purchase and consumption, and more generally, on how we now think about and behave around meals, food, eating and drinking.

Box 1

A personal note

I remember the day in November 2010 when I read the first commentary on ultra-processing published in World Nutrition. I was in the midst of writing my thesis, and wondering about my career. My doctoral research focused on consumption of sweet foods and drinks. My approach was based on the distinction between natural and processed sources of dietary sugars. I was convinced that processed carbohydrates are a central cause of the pandemic of obesity and various chronic diseases, and I could not understand why industrialised, heavily processed foods are rarely the focus of epidemiological and nutritional studies.

Then I came across Carlos Monteiro's first commentary. I was thrilled by the thesis that 'the main public health issue with food is the nature, extent and purpose of processing'. Being trained as an anthropologist, I liked the fact that he is not only talking about nutrition from a biological point of view, but also bringing in society, economics, politics and the environment. I saw the research potential of the new classification of foods. So I wrote to him asking about the possibility of a post- doctoral fellowship in his research team. I suggested starting by studying Canadian dietary patterns, using the new classification.

Six months later I arrived in Brazil, and our Canadian study is going well. In future, I hope to use my knowledge as a social scientist to give new perspectives to our shared work. I hope too that more researchers from related disciplines join us in this important and exciting journey of discovery.

Examples

Before I begin, I want to make clear that this commentary does not comment on or criticise any specific food and drink company, or any specific product. The examples shown are illustrative of a general tendency. All the points made here are generic, concerning the advertising of ultra-processed products in general.

Substance

Most commentary on any type of 'fast' or 'convenience' products tends to focus on their nutrient composition. Typically they are fatty, sugary or salty. But this is only a fraction of the story. We have in-built ' hunger' for sweetness, which signals that fruits are ripe, for fat, to store at times of food shortage, and salt, because in nature foods are generally poor sources of sodium, an issue mostly in hot climates.

Added sugars, fats and salt in sophisticated combinations are therefore all experienced as desirable (10). They can also affect the brain. Intensely sweet products can relieve stress, or dysphoria (depression, discontent, feeling emptiness),by neurotransmission of dopamine and opioids, which in common with various drugs, create a sense of well-being (10-12). Also, chemical and other additives are used not just to preserve products or to make them look, smell and taste good. As one example of many that could be given, the salt substitute and enhancer monosodium glutamate is liable to impede the hypothalamic regulation of appetite (13).

Branding, trademarking

Processed products have been branded for over 150 years. The modern development, is linking company names with the brands of product ranges

Branding has been used ever since industrialisation, and even before then – indeed from time immemorial, if promoting names of makers or products with the purpose of inducing trust, is counted. Branding and trade-marking, whereby names and designs are protected legally, and now may have a value of anything up to $US billions, have been an intrinsic part of the mass manufacture of food and drink products in the early 1800s.

The three pictures at top, above, are of advertisements from around 100 years ago (left, right), and of painted and mounted advertisements on a shop in India, probably dating from the 1970s. In these cases it is the name of the manufacturer that is emphasised. The pictures below are of recent promotions. At left, the logo remains basically the same, and the company name is linked with a brand – a legally protected trade name of the product. The same strategy is followed at right. The picture at centre is of a dispenser of soft drinks in a takeaway or eat-in fast food outlet in the US.

Branding and trade-marking are long-established strategies to sell specific products, and then all products made by a company. These methods are now increasingly used not just to attract parents to foods for their children, but also the children themselves (14). They are designed to tie customers and consumers and their families to the companies and their products.

Almost all products that are branded and trademarked effectively are ultra-processed, with exceptions such as some fresh fruits grown and distributed by giant corporations. One reason is that powerful branding and trade-marking depends on packaging, and other methods of containing processed products, that provide a physical surface for advertisement and promotion. The strategy of transnational corporations that own a range of products is to imprint brand loyalty throughout life. This is most effectively done when parents believe that a branded product formulated for young children has protected the health or even saved the lives of their own children (15).

The sizzle

Here ends the introduction to the specific points made in this commentary. We all surely know that just as the US presidential candidate who gets elected is usually the one that has most money to spend on the campaign, the food or drink corporation with the biggest spends on promotion, usually sells the most products. These days this is done globally, with smart phones and the internet, as well as with the older methods of broadcast and print media, to get the messages across.

Individual leading transnational food and drink product corporations have annual turnovers much the same as the annual gross domestic product of middle-order countries such as Sri Lanka, Slovenia or Tunisia, and far more than most sub-Saharan African countries. Some also each spend well over $US 1 billion a year on advertising – and a multiple of this if all forms of promotion are included. This money, together with vast human and other material resources, is almost all spent with the purpose of persuading the public, and also policy-makers, that ultra-processed products are healthy, which by their nature they are not (5). This impedes rational choices and decisions. Further, manufacturers and their advertisers and promoters are increasingly enabled to make positive health claims for ultra-processed products whose formulation is modified so as to include somewhat less sugar, salt or salt (any of these) or to which synthetic versions of micronutrients are added.

The subliminal sizzle

But the specific purpose of this commentary is to go deeper, and to look at hidden persuasion, much of which is subliminal – beneath consciousness (16). As summarised in Box 2, below, for well over half a century in the US, then soon afterwards in Canada, the UK and other countries, and then worldwide, food advertising and marketing techniques have derived from Sigmund Freud's theories of the irrational and unconscious individual, group and mass mind.

They can be described as giving the substance its sizzle, or as 'sexing up' the product – in a generic sense of the word 'sex', and also specifically.

Box 2

Hidden persuasion: the masterminds

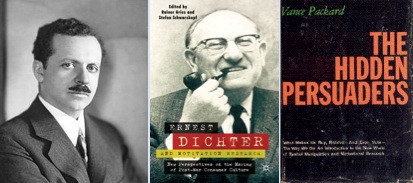

Edward Bernays (left), Ernest Dichter (right): the Austrian-American 'hidden persuaders' who used Freud's theories to mastermind advertising and marketing

Processed food and drink advertising and marketing strategies were developed in the US as a result of the vision and energy of two men: Edward Bernays (1891-1995) as from the 1920s (left, above), and Ernest Dichter (1907-1991) as from the 1940s (right, above). Both were originally Austrian. Both applied Sigmund Freud's theories of the irrational and unconscious mind and its influence on beliefs and behaviour (Bernays was Freud's nephew). They are now generally seen as the founding fathers of the modern methods of advertising, publicity and public relations originated largely in the US and now used worldwide. These are used to shape consumer behaviour, and also to manipulate citizens.

In his book Propaganda (18) Edward Bernays wrote: 'The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government.. .In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons...who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind'. Ernest Dichter had a comparably enormous impact on the development of modern methods of advertising and marketing (19). Like Bernays, he used methods designed to induce people to buy products by addressing underlying desires, wants and emotions.

People just want to have fun

Ultra-processed products are often projected as cool and fun and pleasant

for children, who increasingly push demand for them, and also for adults

The projection of imaginary characters, magnify the attraction of brands. This works most effectively with children, who are now attracted to products by deals done between the manufacturers of ultra-processed products and multi-media entertainment corporations such as Dreamworks™. Products marketed at children frequently project images and notions of coolness and of fun, as shown above. In a 2010 study published by the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, researchers found that more than half of the advertisements for 'fast' and other ultra-processed product advertisements targeted at children used humour and ideas meant to feel fun and cool, to their products (20).

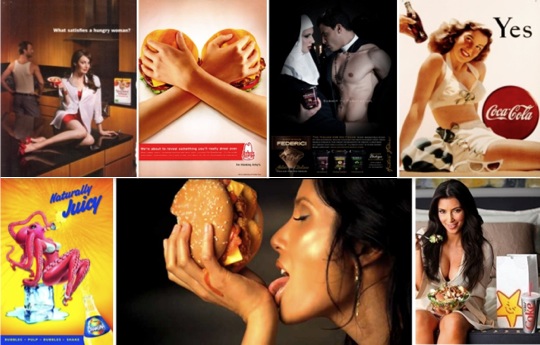

Substitutes for sex

Images and ideas used to promote ultra-processed products exploit sexuality. Some are amusing. Some are bizarre or quasi-pornographic. All are irrelevant

Whenever it seems a good move, the promoters of ultra-processed products will sex up their propaganda in the literal sense. The idea that a fizzy soft drink could increase sexual attraction has been the basis of a very long series of 'classic' such as the 'bottle on the beach' image (top, right), cleverly combining allure with a sense of wholesomeness.

Other puffs for ultra-processed products are strange, like the octopus in a bikini used to promote another soft drink, one of a series that includes a bear, deer, giraffe and hyena in provocative poses. Top left is propaganda for a breakfast cereal, whose selling line is 'what satisfies a hungry woman', and whose image includes what looks like an Italian stallion in an under-vest lurking in the background. The model at bottom right is advertising a fast food meal; the basket in her lap contains salad. A promotion for ice-cream (top, second from right) is of a half-naked man and a model styled as a nun, with the selling line 'submit to temptation'.

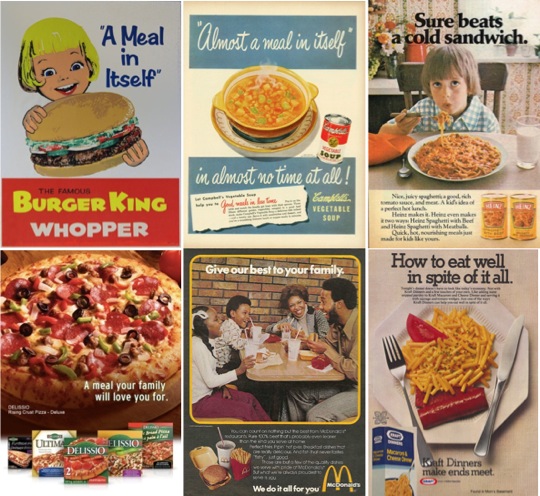

Playing with the family

Advertising of ultra-processed products shapes the ways we think and act around home, gender and family issues, and parent-child relationships

The whole story of human civilisation includes provision of meals for the family, as part of caring and loving relationships, and the offering of hospitality to colleagues and friends. A growing literature strongly suggests that such commensality, in which meals are enjoyed in company round a table, contributes to nutritional health and protection against disease, as well as enhancing well-being (21). In her book Food is Love, Katherine Parkin describes several abiding themes, including the idea that women should love their families through food, the idea that the preparation of meals is empowering, and that women are the providers of the needs of their family (22).

You might think that the central place of the family table in the home, and of cooking and the provision of meals as a binding force for the family, would be impossible obstacles for the manufacturers of ready-to-heat or ready-to-eat packaged products. The pictures above give an indication of how they surmounted this problem. First, you will notice that in all of the pictures, a table is shown or implied, thus giving an illusion of commensality.

Some of the specific images are telling. Those in the top row are of older advertisements. Top centre does suggest food preparation, perhaps of instant oatmeal. But top left, the invention of individual ready-to-eat breakfast cereals, in part to stop the contents becoming limp, as they may in usual-size packets, conveys that young children and even a baby make the choices, while the mother looks on, as the provider who has not prepared anything – hence the folded arms. The advertisement at top right is particularly audacious: here a little boy is praying that God will provide 'chicken' 'nuggets' and French fries, rather than his mother making a cooked meal. The modern images in the bottom row are obviously more comfortable with promoting ways of life in which proper meals have disappeared, and with them conventional family life. The two pictures on the left convey a sense of the woman as provider, having gone to the supermarket. The rather curious advertisement for instant coffee and instant soup, on the right, separates the girl from the young woman; they seem to be unrelated. In these pictures there are no men.

In general the advertisements evoke the natural ties between mothers and their children, and the sense that providing food is a way to express love. But the reality of instant meals, dishes and snacks, often if not usually now consumed alone or while watching television, is of course quite different. The images and themes in the advertisements have no rational meaning. These address the fears, worries, desires, hopes, frustrations and worries about family life and gender roles, by attaching a sense of warmth and bonding to sugary, fatty or salty cheapened edible products. They even imply that instant dishes and snacks continue to play a vital role in the liberation of women – see Box 3.

The end of meals

Ultra-processed ready-to-heat or -to eat dishes or snacks advertised as if

they are real meals, which even increase the bonds of love within families

Politicians in many countries spend a lot of time complaining about the loosening of family ties, the break-up of families, the rise in teenage pregnancies and single-parent households, uncontrolled children, rioting in the streets, the loss of respect and any sense of citizenship, and so on. As far as I know, no politician has noticed the blindingly obvious fact that ultra-processed 'fast' and 'convenience' products, now very heavily advertised throughout the world, are part of this process. They play a major role in the erosion of family life, in favour of individual 'grazing' and snacking. The meal table disappears, and with it family cohesion.

As you can see from the images above, the top row being older, and the bottom row recent, the advertising for such products consistently suggests the complete reverse of this reality. They project the idea that these products are real main meals – 'dinners', in one case – and even that they contribute to family bonding. That is, they play on the hopes and desires in particular of parents, by conveying the impression that they are contributing to what they are in fact displacing. In one case, the family meal table is replaced by a table in a burger outlet, with a very clever selling line – not 'give your best to your family' but 'give our best to your family'. In effect, the company becomes another parent, or even replaces them. See also the generic selling line 'We do it all for you'. So what is left for the father except to pull faces and tell jokes, as if he is merely a bigger brother? Again, see Box 3.

Box 3

'No time to cook'

The people who promote ultra-processed products are united in claiming that these days, we all have no time to prepare and cook meals. They have been saying this since the 1930s. More recently they have been claiming that instant products are an essential part of liberation and equality of women.

Thus, while still in Canada I saw two similar televised advertisements. In one, a man comes back from work and meets his wife. The announcer says that instead of losing time preparing a meal he should buy a ready-to-heat lasagne meal and spend quality time with his loving spouse. In the other, a man is playing street hockey with his boy in front of his house. He rushes into the house leaving his boy alone. The announcer then says that instead of losing time cooking, he should buy a ready-to-heat meal and spend quality time with his kid. Propaganda like this is very skilled. It presses on a sensitive aspect of parent-child relationships.

But do people really not have time to cook? Or is it rather that they have been trained not to value cooking? And what is most valuable? So often we are led to believe that immediate gratification is preferable to longer term goods. In many societies, it is still true that people prefer to spend time appreciating food, and in choosing and preparing it, and enjoying meals in company, for good health, good company and as part of family life.

Last September, just before I left Canada for Brazil, I gave a seminar at the University of Ottawa, and met nutritionists working for Health Canada. We discussed ultra-processed products which, they felt, contribute to the liberation of women. They also felt that my support of meals was unreal, because 'women will never now accept to go back and slave in front of the stove'. But why should the making of meals be only work for women? Men and children can join in too.

What is really happening here is much the same as with the colossal and successful pushing of baby formula. The food manufacturing and associated industries, including those concerning with advertising and promotion, are pushing us all, and in the same general direction. This is to believe that we all can achieve more freedom and happiness by transferring our central tasks of life, including the preparation, cooking and enjoyment of meals, a true sign of love, to – the ultra-processed product industry.

I can't control myself

Much propaganda for ultra-processed products conveys the impression that once you begin to consume them you will lose control. This may be true

As mentioned above, we have built-in hungers for sugar, fat and salt, and once these are separated from their natural matrices in whole food and made into ultra-processed products, they are for this reason liable to be over-consumed. There is also the issue of natural and chemical ingredients and additives that are intensely attractive, either to the senses, or specifically to the brain, and which therefore are quasi-addictive.

So how do the manufacturers of such ultra-processed products, and their advertising and marketing whizz-kids, get round this? They do so by developing the approach used by Salman Rushdie as a young advertising agency copywriter, when he invented the selling line 'naughty but nice' for packaged cream cakes. That is, the general approach is to project compulsive out-of-control consumption and behaviour, which is bad, as thrilling, which is good.

Thus 'it'll blow your mind away' (top row, middle) with an image of a young woman with her eyes and mouth wide open about to receive a burger, as if she is at a rock concert. (Sometimes I wondered if advertisements like this were a joke, but this one is for real, I believe). Thus you see the astounding image of a baby (top, right) boggling at weaning food with a selling line promising the mother than he will eat it all up. You bet he (or she) will! And top left, a type of expensive chip (crisp) is promoted with the line 'once you pop you can't stop'.

Discussion

The issue of loss of control over food choice and consumption is now much discussed, but usually only in the context of children. There is rightly a lot of concern about the fact that children and younger adolescents are vulnerable to food advertising because they do not yet possess the developed behavioural control mechanisms that can self-regulate consumption of food, even when it is highly palatable, visible and marketed (23). It is also said that adolescents lack the brain maturity to resist highly appealing yet unhealthy food, because they want instant rewards, not long-term benefits. Children up to 11-12 years old are very sensitive to the persuasive component of food advertising and often fail to recognise the commercial motivation. (24). More recent research indicates that this vulnerability extends throughout childhood to the age of around 18 (25).

Lifelong loss of control

But I think this evidence, which reinforces the experience of parents and also common sense, applies throughout life. First, conditioning in early life persists, and may well permanently damage appetite and other behaviour control mechanisms. Second, preferring instant gratification from unhealthy but intensely pleasurable products characterises the current 'anything goes' unregulated capitalism.

The myth of 'the market'

The advertising as well as the manufacture of ultra-processed products reveals that in our field certainly, the notion of a 'free market economy' is a myth. In a free market, citizens and customers make informed decisions and rational choices. Is this possible in any society where many billions of dollars and equivalent currency is spent on advertising of products that are intrinsically unhealthy? I suggest not. This environment creates loss of control over food choice and consumption (17-19).

Ultra-processed products are designed and also marketed to be highly appealing and attractive to our inner senses, desires, temptations, emotions, and irrational and unconscious drives. Their advertising and marketing should not be seen as separate from their formation. Product formulation includes promotion. This creates an environment in which customers and consumers give up control of what they buy, eat and drink. It also creates an environment in which the fundamental human activity of preparing and cooking meals for the household and family, with all this implies, is surrendered to Big Food and Big Snack – the transnational manufacturers of ultra-processed, typically calorie-dense, fatty, sugary or salty 'fast' and 'convenience' ready-to-eat or ready-to-heat dishes, snacks and drinks. Is this what we want? Is this the world we wish to leave to your children? I suggest not.

Conclusion

When meals and dishes are no longer prepared and cooked at home, control over food quality and content is lost. When preparing food, we can choose the amount of sugar, fat and salt we use. With ready-to-eat meals and snacks, there is no such control. All we can do is to avoid buying and eating the stuff. This point is surely well understood to us all. Here I go further.

This brief commentary goes further and touches on an issue which I believe to be of fundamental importance to public health nutrition in its biological, and also behavioural, social and other aspects. I am proposing that obesity and various chronic diseases are now pandemic and out of control, in part because the behaviour of transnational and other giant food and drink corporations, and of the people who advertise and promote their products, is also out of control.

One favourite line of ultra-processed product advertisers and promoters is that their work adds to life's rich pageant and to the gaiety of nations, is all good clean honest fun, that some of it has the quality of art, that yes some bad stuff has been perpetrated. But – the argument continues – what's being suggested instead, East Germany before the fall of the Wall? This line has some merit, but not much.

So what is the answer? This commentary is meant to raise the issue, not to resolve it. First, we all should be aware of what has been going on, beginning early last century, but which is vastly more pervasive and universal now.

Progress can be made. For example, I suggest that any advertising or promotion that can be reasonably seen as encouraging compulsive consumption should be made illegal. I suggest also that the advertising and promotion professionals whose techniques include tapping into the unconscious mind should be held to account, by for example being questioned in public by professionals like us, committed to public health, in hearings convened by governments. This democratic and accountable process could be built on foundations such of those of the 1986 Ottawa Charter, linked here. It should lead to rational regulations that protect the health – and I dare say also the general state of mind – most of all of vulnerable people, including children, young people, and parents, throughout the world.

References

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing.[Commentary] World Nutrition, November 2010, 1, 6:237-269.

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing. The good, the bad, and the toxic. [Commentary]World Nutrition, October 2011, 2, 9:496-507.

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing. The hydrogenation bomb. [Commentary] World Nutrition, August 2011, 2, 4:176-194.

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing. Why bread, hot dogs – and margarine – are ultra-processed. [Commentary] World Nutrition, November-December 2011, 2, 10:534-549.

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing. There is no such thing as a healthy ultra-processed product. [Commentary] World Nutrition, August 2011, 2, 7:333-349.

- Contreras J, Garcia M. Alimentacao, sociedade e cultura. Rio de Janeiro: Fiocruz Editions,2011.

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing. Labelling: The fictions [Commentary] World Nutrition, March 2011, 2, 3:136-147.

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing 'Food guide pyramids', and what's the problem with bread. [Commentary] World Nutrition, January 2011, 2, 1: 22-41.

- Monteiro C. The big issue is ultra-processing: the price and value of meals. [Commentary] World Nutrition, June 2011, 2, 6:271-282.

- Gibson E. Emotional influences on food choice: sensory, physiological and psychological pathways. Physiology & Behavior, 2006, 89, 1:53-61.

- Adam T, Epel E. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 2007, 91, 4:449-458.

- Macht M. How emotions affect eating: A five-way model. Appetite, 2008,50, 1: 1-11.

- Hermanussen M, Garcia A, Sunder M, Voigt M, Salazar V, Tresguerres J. Obesity, voracity, and short stature: the impact of glutamate on the regulation of appetite. European Journalof Clinical Nutritrion, 60, 1:25-31.

- Connor S. Food-related advertising on preschool television: building brand recognition in young viewers. Pediatrics, 2006, 8,4:1478-148

- Monteiro C, Gomes F, Cannon G. Can the food industry help tackle the growing burden of under-nutrition? The snack attack. American Journal of Public Health 2010, 100 (6): 975-981.

- Packard V. The Hidden Persuaders. New York: Knopf, 1957.

- Curtis A. The Century of the Self. BBCtv series. 2002. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ The Century of the Self.

- Bernays E. Propaganda. New York: Horace Liveright, 1928.

- Schwarzkopf S, Gries R. Ernest Dichter and Motivation Research: New Perspectives on the Making of Post-war Consumer Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Harris J, Schwartz M, Brownell K. Fast Food Facts: Evaluating Fast Food Nutrition and Marketing to Youth. New Haven: Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity, 2010.

- Fischler C. Commenality, society and culture. Social Science Information 2011, 50 (3-4), 1-21.

- Parkin K. Food is Love : Food Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

- Harris J, Graff S. Protecting young people from junk food advertising: Implications of psychological research for First Amendment law. American Journal of Public Health, 2012, 102, 2:214-222.

- Carter O, Patterson L, Donovan R, Ewing M, Roberts C. Children's understanding of the selling versus persuasive intent of junk food advertising: implications for regulation. Social Science & Medicine, 2011, 72, 6:962-968.

- Dosenbach N, Nardos B, Cohen A, et al. Prediction of individual brain maturity using fMRI. Science 2010, 329, 1358-1361. Erratum in: Science 2010; 330: 756

Acknowledgement and request

Readers are invited please to respond. Please use the response facility below. Readers may make use of the material in this editorial if acknowledgement is given to the Association, and WN is cited

Please cite as: Moubarac, J-C. The big issue is ultra-processing. Sexing up ultra-processed products. [Commentary] World Nutrition, March 2012, 3, 3: 62-80. Obtainable at www.wphna.org

The opinions expressed in all contributions to the website of the World Public Health Nutrition Association (the Association) including its journal World Nutrition, are those of their authors. They should not be taken to be the view or policy of the Association, or of any of its affiliated or associated bodies, unless this is explicitly stated.

I thank above all, Carlos Monteiro and Geoffrey Cannon, who have supported and guided me at all stages of preparation of this commentary. I regard them as my co-authors. WN commentaries are subject to internal review by members of the editorial team.